Case Presentation:

A 60 year-old male with hypertension and hyperlipidemia is evaluated in the CCU for transient left-sided hemiparesis 72 hours following successful percutaneous intervention of a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI). On admission, emergent left heart catheterization showed total occlusion of his mid left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, which was successfully stented. Post-procedure transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed an estimated ejection fraction of 25% with complete apical akinesis. The patient’s neurologic symptoms resolve within 15 minutes, consistent with transient ischemic attack (TIA). Repeat TTE with contrast after TIA redemonstrates complete apical akinesis, as well as a mobile mass concerning for an LV apical thrombus.

Ask Yourself:

Questions:

1. What are the risk factors for development of a left ventricular thrombus?

2. What is the diagnostic approach for a left ventricular thrombus?

3. What is the management of a left ventricular thrombus?

4. Is there any utility in prophylactic treatment against LV apical thrombus?

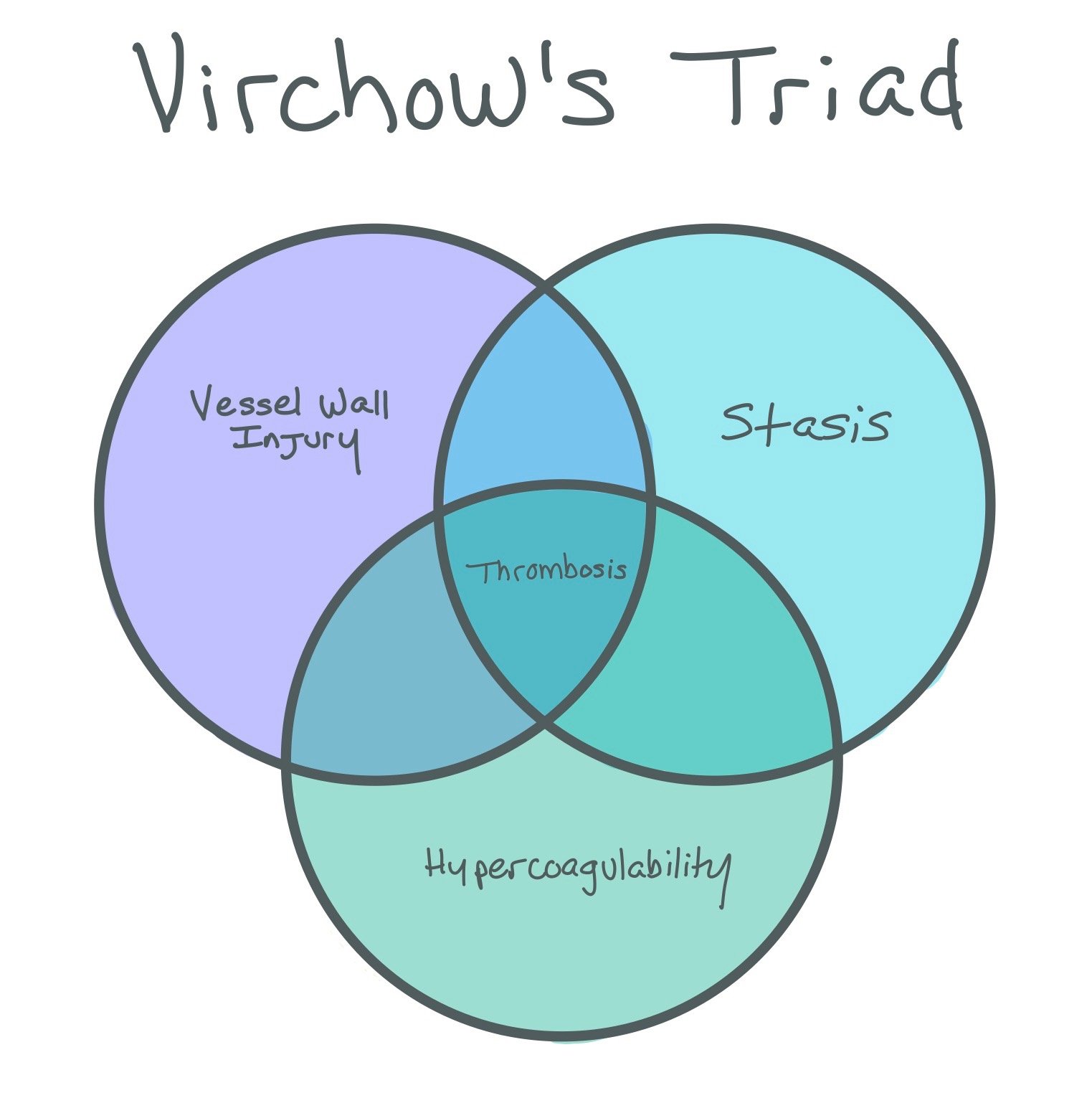

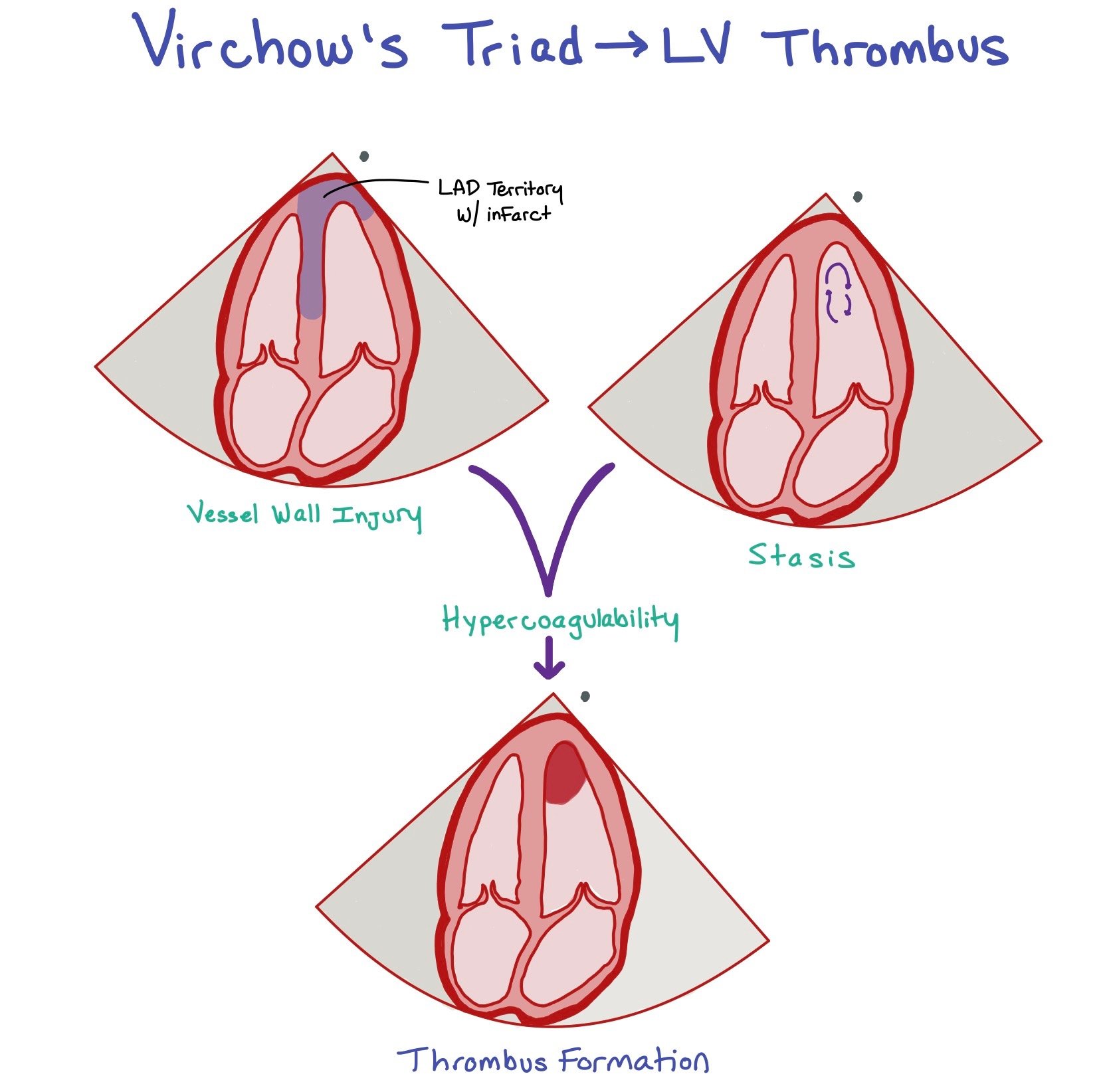

This figure shows a left anterior descending (LAD) infarct. Since the LAD supplies the apex of the heart, an LAD infarct can cause LV region wall akinesis with decreased LV function (1). Due to the infarction, the patient will have scar formation due to the subendocardial injury (2) and be in a hypercoagulable state (3). These three factors comprise Virchow’s triad, which can ultimately lead to left ventricular (LV) thrombus formation (seen in the picture at the bottom).

Background:

In the setting of an MI involving the LV wall, the combination of hemostasis from regional wall akinesia, direct subendocardial injury from ischemia, and inflammatory state with scar formation during the acute coronary syndrome generates a major risk factor for thrombotic events, also known as Virchow’s triad. While reperfusion strategies have dramatically improved survival outcomes following acute MI, post-infarct complications, including LV thrombosis, still leads to significant morbidity and mortality. LV thrombi can lead to arterial embolic events including stroke, TIA, and limb ischemia.

Culprit lesions are typically due to LAD infarcts. The greater the infarct and the longer it takes to get good reperfusion, the more scar that is formed and the more likely it is the patient will develop an LV thrombus.

LV thrombi can form within 24 hours after acute MI, and 90% are formed within 2 weeks of the event. Incidence data in the post-PCI era is limited, with retrospective studies suggesting an overall rate of 4-8% for development of an LV thrombus after reperfusion for ST-elevation MI. Major risk factors include large infarct size, apical akinesis or dyskinesis, LV aneurysm, and anterior MI.

TTE plays a key role in the detection of LV thrombi given its ubiquitous use in patients undergoing evaluation for STEMI. Under ideal circumstances, TTE has high specificity (>90%) in diagnosing LV thrombus, which can be visualized as a discrete echodense mass in the left ventricle adjacent to an area of the LV wall which is hypokinetic or akinetic. In cases where the LV apex cannot be adequately assessed, the use of IV contrast-enhanced TTE improves the diagnostic accuracy. Since the contrast does not penetrate the thrombus, there should be no dye extravasation within the clot itself. This contrasts with a tumor which is innervated by multiple blood vessels and will light up with contrast once it is injected. We do not tend to use TEEs to detect thrombi as they do not help to better assess the LV apex.

The best imaging modality for assessing an LV thrombus is a late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MRI. Studies have shown that patients with LV thrombi have an increased risk of both short (6 months) and long term (3 years) cardio-embolic events. When compared with cardiac MRI, TTE with contrast was actually found to have a very low sensitivity for detecting LV thrombi (~29%). The LV thrombi that are only seen on cardiac MRI and NOT TTEs with contrast tend to be small and mural in morphology.

Ultimately, in cases of diagnostic ambiguity, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with late gadolinium enhancement is considered the diagnostic gold standard for detection of LV thrombus.

If a patient gets a TTE with questionable LV thrombus or if there is high clinical concern for a thrombus given a cardioembolic event, it is reasonable to pursue a cardiac MRI.

The figure depicts an LV thrombus (red arrow) in both a cardiac MRI with late gadolinium enhancement (left) vs transesophageal echocardiogram (right). Note how the thrombus appears black in both pictures as there is no dye extravasation within the thrombus. Picture courtesy of Levine et al, Circulation. 2022;146:e205–e223

Patients are at an increased risk for LV thrombus when they have severe LV systolic dysfunction, increased myocardial scar burden, apical wall motion abnormalities, history of acute cardioembolic events, and an LV aneurysm.

Although cMRI is the gold standard, there are barriers to getting this imaging. Specifically, the patient has to be stable enough to get the images, they have to be able to lay down flat and hold their breaths long enough to get ood images, and there has to be an available scanner and cardiologist who is skilled at reading cMRIs. Sometimes the patient’s body habitus can also limit them from fitting in the scanner.

Ultimately, since the risk for developing an LV thrombus is greatest 2 weeks after MI, a focused TTE might be considered at this time to evaluate for thrombus formation.

Complications / Interventions:

Embolization may occur prior to one of these end outcomes, with most events occurring within the first three months. The overall risk of an embolic event in patients with an LV thrombus not on anticoagulation is reported to be 10 to 15%.

Anticoagulation therapy in patients with LV thrombus is aimed at reducing the risk of systemic thromboembolic events. Current guidelines give a class IIa recommendation to treat LV thrombus with warfarin for a minimum of 3-6 months. To date, no randomized controlled trial has compared anticoagulation with warfarin against direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), although guidelines and expert opinion suggest that DOACs are a reasonable alternative for initial treatment.

Guidelines give a class IIa recommendation for repeat imaging at the end of the treatment period to evaluate for resolution of LV thrombus. In the case of resolved or endothelialized thrombus, it would be appropriate to discontinue anticoagulation. In the case of persistent thrombus, anticoagulation should be continued with consideration of an alternate agent.

Anticoagulation in LV Thrombus:

Patients who develop an LV thrombus should be anticoagulated with either warfarin or a DOAC for at least 3-6 months after LV thrombus is seen on imaging. Repeat imaging with the same modality in which the original LV thrombus was originally seen should be done after this time period (>3 months). If the LV thrombus is no longer seen and there is improvement of LV systolic function, shared decision making should be done to potentially stop anticoagulation. In patients who develop an LV thrombus significantly after original MI, they should also be anticoagulated for 3-6 months with repeat imaging at that time; however, these patients may be candidates for longer courses of anticoagulation. Patients who do get oral anticoagulation and are on DAPT should only continue this triple therapy for 1-4 weeks total due to increased bleeding risk.

If patients have embolic events, Neurology should be consulted prior to initiation of anticoagulation due to concern for hemorrhagic conversion of the ischemic stroke. Overall, starting anticoagulation will be dependent on stroke severity; meaning, the smaller the stroke, the earlier we can start anticoagulation due to lower concerns for hemorrhagic conversion. For severe strokes, studies suggest waiting to start anticoagulation 4-12 days after initial event. If a patient has a known LV thrombus and just had a stroke, we might favor starting anticoagulation a little sooner due to very high risk of recurrent strokes.

Role of prophylaxis:

For patients who are at high risk for developing LV thrombus due to their recent LAD infarcts with apical akinesis and reduced EF, the questions is if they should get prophylactic anticoagulation. Unfortunately, there have not been randomized control trials that have specifically investigated full dose anticoagulation to prevent LV thrombus formation. In the few studies that have been done to date, patients who were anticoagulated had higher risks of bleeding without reduction of arterial embolization or death. As these patients are already on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), this would mean adding a third agent for anticoagulation, which would greatly increase bleeding risk. While there is no data to support adding this third agent, the ACC/AHA guidelines do recommend keeping it on for 1-3 months if added as clot formation risk is highest within the first month post MI.

Back To The Case:

Given the finding of a LV thrombus in our patient who had a transient ischemic attack, anticoagulation should be started, and he begins apixaban in addition to his other post-MI medications.

1. What are the risk factors for development of a left ventricular thrombus?

Think Virchow’s Triad. Any time there is vessel wall injury, venous stasis, and hypercoagulability, this can cause thrombus formation. When patients have heart attacks, this causes vessel wall injury and resultant decreased EF. When there’s apical akinesis, this allows for stasis of the blood that creates a hypercoagulable state. Together, this makes a ripe situation for a thrombus to form in the LV.

2. What is the diagnostic approach for a left ventricular thrombus?

The best way to diagnose an LV thrombus is to get a TTE. A TTE has a high specificity (>90%) in diagnosing an LV thrombus, which can be visualized as a discrete echo-dense mass in the left ventricle adjacent to an area of the LV wall which is hypokinetic or akinetic. In cases where the LV apex cannot be adequately assessed, the use of IV contrast-enhanced TTE may improve the diagnostic accuracy.

3. What is the management of a left ventricular thrombus?

Back to our patient, given the finding of a LV thrombus who had a transient ischemic attack, anticoagulation should be started, and he begins apixaban in addition to his other post-MI medications. Follow-up TTE should be scheduled after completion of his initial course of anticoagulation. If the thrombus has resolved or endothelialized, it would be appropriate to discontinue anticoagulation. Anticoagulation therapy in patients with LV thrombus is aimed at reducing the risk of systemic thromboembolic events. Current guidelines give a class IIa recommendation to treat LV thrombus with warfarin for a minimum of 3-6 months.

4. Is there any utility in prophylactic treatment against LV apical thrombus?

Unfortunately, there have not been randomized control trials that have specifically investigated full dose anticoagulation to prevent LV thrombus formation. In the few studies that have been done to date, patients who were anticoagulated had higher risks of bleeding without reduction of arterial embolization or death.

Further Learning:

Resident Responsibilities

LV thrombus should be considered in patients with an anterior STEMI, known infarction of the LAD, or large infarction defined by LV ejection fraction less than 30%.

TTE is the initial test that will detect the majority of LV thrombi, but cardiac MRI is the gold standard in case of diagnostic ambiguity.

DOACs are considered good alternatives for VKA. As there is no data on DOAC vs VKA for ESRD patients with LV thrombi, choice of anticoagulation needs to be made on a case-by-case situation.

In the absence of contraindications, patients with an LV thrombus and recent MI should be anticoagulated for a minimum of 3 months with either DOAC or warfarin. Repeat imaging should be done at 3 months. If there is clot resolution, then it is reasonable for anticoagulation to be stopped.

When patients have a more distant history of MI and develop an LV thrombus, guidelines recommend minimum 3-6 months of anticoagulation therapy and to only discontniue if EF >35% or patient has major bleeding prohibiting anticoagulation.

Attending and Fellow Pearls

Per guidelines, we do not routinely prophylactically anticoagulate patients who are at high risk of developing LV thrombi. However, patients with takotsubo syndrome, LV noncompaction, eosinophilic myocarditis, cardiac amyloid, and pericartum cardiomyopathy may be at higher risk for developing LV thrombi. Therefore, determination of whether or not to anticoagulate these patients and for how long should be done on a case-to-case basis.

Thrombi can be classified as mural (i.e laminated or having its borders contiguous with the adjacent endocardium) or protuberant (meaning the borders are distinct from the adjacent endocardium). Mural thrombi are best seen with TTE with IV contrast as the thrombi will not take up the contrast and can be more readily appreciated.

If the patient continues to have an LV thrombus despite multiple months of anticoagulation (>3 months), it is reasonable to change anticoagulation strategies and to reassess the clot in a few months. However, if the clot is a mural thrombus and it has become organized or calcified, per the AHA guidelines, it is “not unreasonable” to discontinue anticoagulation.

Further Reading

Management of Patients at Risk for and with Left Ventricular Thrombus: A Scientific Statement from the AHA

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001092

The above decision algorithm was taken from the AHA’s “Management of Patients at Risk for and with Left Ventricular Thrombus,” Levine et al.

How’d we do?

The following individuals contributed to this topic: Ryan Sun, MD, Mary Rodriguez Ziccardi, MD

Chapter Resources

Delewi R, Zijlstra F, Piek JJ. Left ventricular thrombus formation after acute myocardial infarction. Heart 2012;98:1743-1749.

Levine GN, McEvoy JW, Fang JC, Ibeh C, McCarthy CP, Misra A, Shah ZI, Shenoy C, Spinler SA, Vallurupalli S, Lip GYH; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Management of patients at risk for and with left ventricular thrombus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online ahead of print September 15, 2022]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001092

Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D, Kamel H, Kernan WN, Kittner SJ, Leira EC, Lennon O, Meschia JF, Nguyen TN, Pollak PM, Santangeli P, Sharrief AZ, Smith SC Jr, Turan TN, Williams LS. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021 Jul;52(7):e364-e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375. Epub 2021 May 24. Erratum in: Stroke. 2021 Jul;52(7):e483-e484. PMID: 34024117.

Cruz Rodriguez JB, Okajima K, Greenberg BH. Management of left ventricular thrombus: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Mar;9(6):520. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-7839. PMID: 33850917; PMCID: PMC8039643.

Camaj A, Fuster V, Giustino G, et al. Left Ventricular Thrombus Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Mar, 79 (10) 1010–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.011

Robinson AA, Trankle CR, Eubanks G, et al. Off-label Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared With Warfarin for Left Ventricular Thrombi. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(6):685–692. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0652

Kimura, Shunsuke, et al. “Practical ‘1-2-3-4-Day’ Rule for Starting Direct Oral Anticoagulants After Ischemic Stroke With Atrial Fibrillation: Combined Hospital-Based Cohort Study.” Stroke (1970), vol. 53, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1540–49, https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036695.