Case Presentation:

A 65-year-old male with history of DM, HTN, HLD, CKD presents to the hospital for an elective cholecystectomy. His baseline EKG demonstrates sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 65. He has never been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Home medications include lisinopril, atorvastatin, metformin, and semaglutide. You get the following EKG:

1. Would this patient qualify for a beta blocker prior to surgery for prevention of post-operative atrial fibrillation?

2. If this patient developed postoperative atrial fibrillation, would a rate or rhythm control be the preferred strategy?

3. If this patient developed postoperative atrial fibrillation, would you anticoagulate him and if so, how long would you keep the patient on anticoagulation?

New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation Post-Operatively:

Background:

Prevalence: Usually an asymptomatic, self-terminating event that occurs in ~30% of patients after cardiac surgery, ~15% of patients after thoracic surgery, and ~0.4-15% of patients after non-cardiac surgery

Risk factors: Male, age, CKD, HTN, sepsis, HF, valvular heart disease

Adverse events: Association with hospitalization for heart failure, mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction, and non-surgical atrial fibrillation

Pathophysiology:

Sympathetic activity during surgery leads to catecholamine release and tachycardia which predisposes the myocardium to arrhythmia

Electrolyte derangements, electrophysiologic disturbances, transient hypoxemia, and right atrial stretching from intraoperative fluids can all contribute to arrhythmia

Particularly in cardiac surgery, direct manipulation of atrial tissue, inflammation, and myocardial ischemia can lead to post-operative atrial fibrillation

Prevention:

Prophylactic use of beta blockers

Noncardiac surgery: Prophylactic use of beta blockers should not be used for prevention of post-op afib due to increased risk of death

Cardiac surgery: Prophylactic beta blocker or amiodarone is recommended for prevention of post-op afib

Other medications: Evidence for calcium channel blockers, magnesium, colchicine, statins, steroids, polyunsaturated fatty acids is limited or mixed

Rate vs Rhythm Control:

Rate vs Rhythm Control:

Hemodynamically unstable: Cardiovert patient

Hemodynamically stable:

Both are reasonable strategies.

Some data suggesting that an initial strategy of rate control avoids the toxic effects of amiodarone but with slower resolution of atrial fibrillation. No difference in in-hospital stay, survival, or serious adverse events at 60-day follow up between those treated with rate vs rhythm control strategy

Important to note that most patients return to sinus rhythm at discharge, though there is a high rate of long-term recurrence

Tailor approach to the patient: Can consider rhythm control particularly for symptomatic patients despite rate control, those with low ejection fraction, those who cannot achieve rate control, or those who have not converted within 24 hours and would like to avoid anticoagulation.

Anticoagulation:

The use of anticoagulation after postoperative atrial fibrillation is controversial. Per AHA/ACC/HRS guidelines “It is reasonable to administer antithrombotic medication in patients who develop POAF, as advised for non-surgical patients. However, a new study shows that there may be a disadvantage to giving patients with POAF anticoagulation!

Prior study has demonstrated those with postoperative afib are at increased risk of stroke. One study demonstrated that those treated with oral anticoagulation had a lower risk of stroke. However, subsequent study demonstrated an association between discharge anticoagulation and increased mortality.

Some experts suggest anticoagulating those with multiple episodes of afib or single episode >48 hours based on CHA2DS2-VASc Score ≥2 for at least 4 weeks. After 4 weeks, re-assess risks, benefits, patient preference of anticoagulation. Can also consider ambulatory monitoring to assist in decision making.

For patients who are electrically cardioverted, anticoagulation is recommended for 3-4 weeks afterward due to persistent atrial stunning after cardioversion

Remember!! If a patient is cardioverted, they will need to be anticoagulated for at least 4 weeks due to atrial stunning!

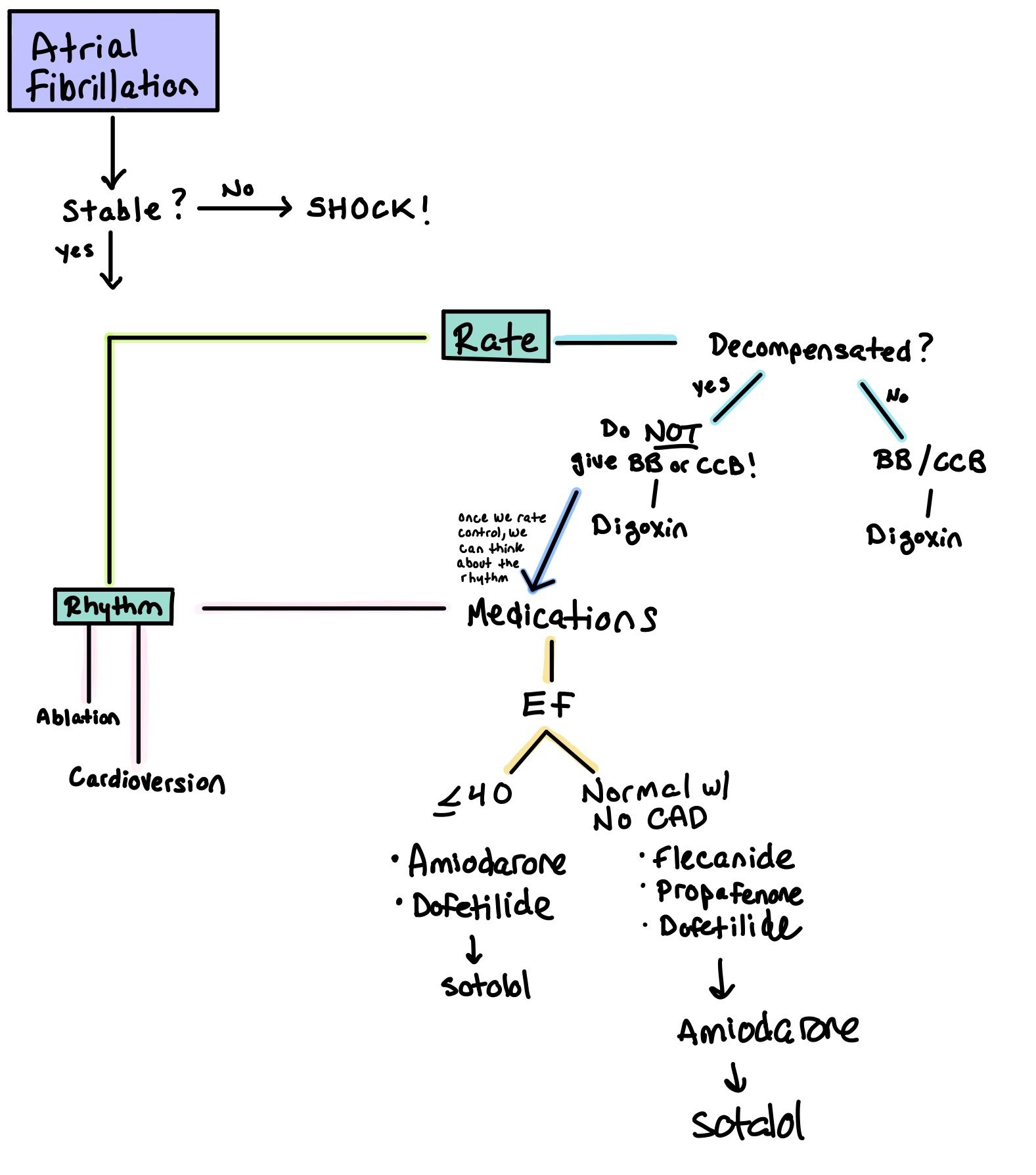

When patients are in AF, the first step is to determine whether or not the patient is stable. If the answer is no, SHOCK!

Remember, all patients who get shocked need to be on anticoagulation for at least 1 month as cardioversion causes atrial stunning.

The next step is to determine if the patient should have rate or rhythm control. Ultimately, rhythm control has been shown to be superior to rate control (EAST-AFNET 4). However, in the acute setting, rate control may be used.

Rate Control:

Is the patient decompensated?

If yes, do NOT give beta blockers or calcium channel blockers!! This will only decompensate them more. If you do, give SHORT ACTING (such as esmolol).

If no, try a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker.

Regardless, digoxin can be used when all other rate control fails.

Medications:

Class 1C: Blocks Na channels; decreases conduction velocity and impulse formation.

Note: These medications MUST be used with a beta blocker or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker to prevent conversion of afib into 1:1 atrial flutter.

Flecainide:

Pro: Relatively safe for patients who have structurally normal hearts

Con: Cannot be used in patients with structurally abnormal hearts

Dosing: PO 50-200 mg Q12h

Considerations: For patients who have a very low burden of afib, flecainide can be taken as a PRN when patients feel they are in afib, aka as Pill in Pocket. Note: they should not take more than 1 dose in 24 hours. Dosing 200 mg (weight < 70 kg) or 300 mg (weight ≥ 70 kg) PRN for paroxysmal AF

Propafenone

Dosing:PO IR 150-300 mg Q8h, ER 225-425 mg Q12h

Considerations: Pill-in-pocket: IR 450 mg (weight < 70 kg) or 600 mg (weight ≥ 70 kg) PRN for paroxysmal AF (no more than 1 dose in 24h)

In the CAST investigation, class 1C antiaarhythmics (flecanide and encainide) were associated with an increased mortality in patients with recent MI. Of note, most of these patients had EF <50%. In CASH, propafenone shown to have similar effects. As such, guidelines recommend that patients with previous MI or significant structural heart disease do NOT get prescribed 1C agents due to concerns for increased mortality and worsening heart failure.

Class II: Prolongs phase 4 of the action potential, causing increased conduction time and refractory periods. Also blocks sympathetic input to the SA and AV nodes

Beta blockers (metoprolol, carvedilol)

Pro: Come in PO and IV form. Works relatively quickly

Con: Will stay in the system and can cause bradycardia and hypotension. Can cause heart block. As these are negative chronotropic agents, they should be used with caution in patients with acute heart failure.

Dosing: Can give up to

Carvedilol up to 25mg BID

Metoprolol 200mg/day or 1mg/kg/day

Considerations:

Cardioselective: atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, nadolol

Class III antiarrhythmics: blocks K channels, causing delayed repolarization; prolongs QTc interval

Amiodarone

Pros: Has both alpha and beta blocking properties and affects Na, K, and Ca channels. Very easy to use. Can be used in patients with structural heart disease. Comes in both oral and IV formulation. Very long half life so good in patients who miss doses

Cons: Many side effects, including thyroid, liver, and lungs. Will be in the system for a very long time

Dosing: 150 mg IVPB, followed by IV infusion 1 mg/min x 6 hrs, then 0.5 mg/min x 18 hrs. May complete 6-10 g load with PO amiodarone once arrhythmia suppressed

Considerations: If arrhythmia does not terminate within 10 min after end of 150mg IV infusion, you can repeat this bolus a second time.

Obtain a baseline chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests (including diffusion capacity), TSH, and LFTs when amiodarone therapy is initiated. Repeat history, physical exam, and chest X-ray every 3 to 6 months.

Dofetilide

Pro: Safe to use in patients with heart failure

Cons: High risk of torsades, with higher risks if medication is not adjusted for renal function. Therefore, patients need to be admitted to the hospital during the first 3 days of initiation to monitor the QTc.

Dosing: Dependent on renal function. With normal renal function, initial dosing is 500 mcg twice daily (maximum dose: 500 mcg twice daily).

Considerations: QTc interval should be measured 2 to 3 hours after the first 5-6 doses. For any QTc prolongation >15% or >500ms, dose adjustments must be made. If there is too much prolongation, this may preclude the patient from getting this medication.Must get EKG, BMP, Mg, and Phos every 3-6 months after administration to monitor QTc, Cr, and electrolytes.

Ibutilide

Dosing: IV infusion 0.01 mg/kg over 10 min (weight < 60 kg) or 1 mg/kg over 10 min (weight ≥ 60 kg)

Considerations: •Acute chemical cardioversion only, not indicated for chronic maintenance therapy

•Discontinue as soon as arrhythmia terminates or marked QTc prolongation occurs

•Do not use in pts with hemodynamic instability

•Give pre- and post-infusion IV magnesium to reduce TdP risk (suppresses early after-depolarizations)

•Monitoring:

•Pre-infusion Mg level (goal ≥ 2 mmol/L)

•Requires continuous ECG during infusion AND at least 4 hours post-infusion due to high risks of Torsades. Make sure patient does not have hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia as this increases torsades risk!

•Have crash cart at bedside

Sotalol: Beta-blocker that helps to slow heart rate and AV conduction, as well as prolong atrial and ventricular action potentials

Pros:

Cons: High risk of torsades. Patients need to be hospitalized during initiation of this drug due to potential QTc prolongation

Dosing: Dosing is renal dependent. For patients with normal renal function, start with 80mg BID. If this dose does not prolong QTc >500 after 3 days, can increase up to 160mg BID

Considerations:

Should NOT be used in patients with HFrEF (EF<40%) as they are most likely also taking an additional AV nodal blocker (i.e. a beta blocker) and this can cause brady or tachy arrhythmias.

QTc interval should be measured 2 to 3 hours after the first 5-6 doses. For any QTc prolongation >15% or >500ms, dose adjustments must be made. If there is too much prolongation, this may preclude the patient from getting this medication.

Must get EKG, BMP, Mg, and Phos every 3-6 months after administration to monitor QTc, Cr, and electrolytes.

Class IV: block L-type calcium channels to delay AV nodal firing

Non-dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers (diltiazem, verapamil)

Pro:

Lower incidence of patient discomfort (dyspnea, chest tightness, flushing)

•2017 Cochrane review showed similar conversion rates to NSR compared to adenosine, without significant differences in adverse drug reactions

Con:

As these are negative chronotropic agents, they should be used with caution in patients with acute heart failure.

May potentially be associated with more hypotension

Slower onset (3-5 min)

Longer duration of action (2-5 hrs) and not preferred in patients who are hemodynamically unstable

Dosing:

Diltiazem: IV bolus 0.25 mg/kg (~20 mg) over 2 min, may repeat 0.35 mg/kg (~25 mg) IVP at 15 min

Verapamil: : IV bolus 2.5-5 mg over 2 min, may repeat with 5-10 mg at 15 min

Class V:

Digoxin: Stimulates the vegas nerve and causes AV node inhibition

Pro: Used for patients who have afib whose rates are not controlled on other agents. The positive inotropic properties make it advantageous for HFrEF patients as it has minimal impact on blood pressure

Con: Toxicity can occur even at therapeutic levels if patients develop AKIs or hypokalemia. Has a VERY narrow therapeutic index (<2 ng/ml)

Dosing:0.25 to 0.5 mg once; repeat doses of 0.25 mg every 6 hours to a maximum of 1.5 mg over 24 hours. For more specific weight based dosing, you can visit https://clincalc.com/Digoxin/

Considerations: Look out for digoxin toxicity! Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances (yellow or blurred vision), and lethargy. Patients can also develop arrhythmias, such as paroxysmal atrial tachycardia, all types of AV block, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation.

Back to the Case:

1. Would this patient qualify for a beta blocker prior to surgery for prevention of post-op atrial fibrillation?

For non-cardiac procedures (as in the case of this patient), starting a beta blocker for prophylaxis of post-operative atrial fibrillation is not indicated due to increased risk of mortality. If this patient were undergoing a cardiac surgery, beta blocker would be indicated.

2. If this patient developed post-operative atrial fibrillation, would rate or rhythm control be the preferred strategy?

Either strategy is reasonable for management of post-operative atrial fibrillation with no difference in 60-day adverse outcomes and mortality between these two groups. Most patients will revert to sinus rhythm without intervention within 24 hours, but a rhythm control strategy can be considered for those who cannot achieve rate control, those symptomatic despite rate control, those who cannot be on anticoagulation and have not converted within 24 hours.

3. If this patient developed post-operative atrial fibrillation, would you anticoagulate him and if so, how long would you keep the patient on anticoagulation

Guidelines suggest it is reasonable to initiate anticoagulation in patients with post-operative atrial fibrillation, though data are mixed. Some experts suggest anticoagulating patients with multiple episodes of atrial fibrillation or a single episode >48 hours if the CHA2DS2-VASc Score ≥2. This patient has a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 and would consider anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks, if atrial fibrillation episodes per above criteria.

Further Learning:

Resident Responsibilities

If there are no contraindications, consider a beta blocker in any patient that will be undergoing cardiac surgery.

Electrically cardiovert all hemodynamically unstable patients.

In the hemodynamically stable patient, discuss with your fellow or attending pursuing a rate vs rhythm control strategy for patients with post-operative atrial fibrillation.

Assess the stroke and bleeding risk for all patients with post-operative atrial fibrillation and discuss with the team the risks and benefits of initiating anticoagulation for a given patient.

Patient who have been electrically cardioverted should continue anticoagulation for 3-4 weeks afterward due to persistent atrial stunning.

Despite returning to sinus rhythm before discharge, at least 30% of patients who develop afib in the hospital will go back into afib post discharge. As such, sending patients home with cardiac monitors has been proven to be the best tool to diagnose afib.

High Yield Trials:

POISE Trial: Those treated peri-operatively with metoprolol vs placebo prior to non-cardiac surgery had higher mortality and rates of stroke

Rate Control vs Rhythm Control for Atrial Fibrillation after Cardiac Surgery: neither rate or rhythm control demonstrated clinical advantage over the other

Anticoagulation in New Onset AF: There may be harm in giving these patient’s anticoagulation!!

Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment: helpful review of post-operative atrial fibrillation

AFFIRM trial: In patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, there is no difference between rate vs. rhythm control

EAST-AFNET 4 trial: Patients with atrial fibrillation who were treated with early rhythm-control strategy had decreased cardiac risk factors, such as stroke, heart failure hospitalization, or cardiovascular mortality.

Attending Pearls

CHADS2-VASc was NOT derived from patients with POAF! Therefore, applying this to post-op patients may be quite inappropriate.

How’d we do?

The following individuals contributed to this topic: Pooja Nayak, MD; Isaac Whitman, MD; Stephanie Vamenta, MD; Stephanie Dwyer, PharmD; Jinjoo Chung, PharmD

Resources

Gaudino, M., Di Franco, A., Rong, L. Q., Piccini, J., & Mack, M. (2023). Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment. European Heart Journal, 44(12), 1020-1039.

Hindricks, G., Potpara, T., Dagres, N., Arbelo, E., Bax, J. J., Blomström-Lundqvist, C., ... & Watkins, C. L. (2021). 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. European heart journal, 42(5), 373-498.

POISE Study Group. (2008). Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 371(9627), 1839-1847.

Arsenault, K. A., Yusuf, A. M., Crystal, E., Healey, J. S., Morillo, C. A., Nair, G. M., & Whitlock, R. P. (2013). Interventions for preventing post‐operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

Khan, M. F., Wendel, C. S., & Movahed, M. R. (2013). Prevention of Post–Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) Atrial Fibrillation: Efficacy of Prophylactic Beta‐Blockers in the Modern Era: A meta‐analysis of latest randomized controlled trials. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 18(1), 58-68.

Mitchell, L. B., Exner, D. V., Wyse, D. G., Connolly, C. J., Prystai, G. D., Bayes, A. J., ... & Maitland, A. (2005). Prophylactic oral amiodarone for the prevention of arrhythmias that begin early after revascularization, valve replacement, or repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 294(24), 3093-3100.

Gillinov, A. M., Bagiella, E., Moskowitz, A. J., Raiten, J. M., Groh, M. A., Bowdish, M. E., ... & Mack, M. J. (2016). Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(20), 1911-1921.

Spragg, D. Atrial Fibrillation in Patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. In: UpToDate. Updated 2022.

January, C. T., Wann, L. S., Alpert, J. S., Calkins, H., Cigarroa, J. E., Cleveland, J. C., ... & Yancy, C. W. (2014). 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 64(21), e1-e76.

Butt, J. H., Xian, Y., Peterson, E. D., Olsen, P. S., Rørth, R., Gundlund, A., ... & Fosbøl, E. L. (2018). Long-term thromboembolic risk in patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA cardiology, 3(5), 417-424.

Riad, F. S., Grau-Sepulveda, M., Jawitz, O. K., Vekstein, A. M., Sundaram, V., Sahadevan, J., ... & Sabik, J. (2022). Anticoagulation in new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation: An analysis from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Heart Rhythm O2, 3(4), 325-332.

Echahidi, N., Pibarot, P., O’Hara, G., & Mathieu, P. (2008). Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51(8), 793-801.

Walkey, A. J., Evans, S. R., Winter, M. R., & Benjamin, E. J. (2016). Practice patterns and outcomes of treatments for atrial fibrillation during sepsis: a propensity-matched cohort study. Chest, 149(1), 74-83.

Čihák, R., Haman, L., & Táborský, M. (2016). 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Cor et vasa, 6(58), e636-e683.

Reddy, V., Taha, W., Kundumadam, S., & Khan, M. (2017). Atrial fibrillation and hyperthyroidism: a literature review. Indian heart journal, 69(4), 545-550.

Silversides, C. Supraventricular Arrhythmias During Pregnancy. In: UpToDate. Updated 2022.

Riad FS, Grau-Sepulveda M, Jawitz OK, Vekstein AM, Sundaram V, Sahadevan J, Habib RH, Jacobs JP, O'Brien S, Thourani VH, Vemulapalli S, Xian Y, Waldo AL, Sabik J. Anticoagulation in new-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation: An analysis from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Heart Rhythm O2. 2022 Jun 16;3(4):325-332. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2022.06.003. PMID: 36097451; PMCID: PMC9463707.